Who's Afraid of Red Scare?

Review of Harper's/Red Scare's controversial event, "Whither Contemporary Art?" on the failings of contemporary art. And an interview with art critic Dean Kissick who started it all.

“It cannot become old-fashioned because it is not part of a fashion.” Preface to the Decoration Designs of Francis Crease, Evelyn Waugh.

“Beware of identity politics. I'll rephrase that: have nothing to do with identity politics. I remember very well the first time I heard the saying ‘The Personal Is Political.’ It began as a sort of reaction to defeats and downturns that followed 1968: a consolation prize, as you might say, for people who had missed that year. I knew in my bones that a truly Bad Idea had entered the discourse. Nor was I wrong. People began to stand up at meetings and orate about how they ‘felt’, not about what or how they thought, and about who they were rather than what (if anything) they had done or stood for. It became the replication in even less interesting form of the narcissism of the small difference, because each identity group begat its sub-groups and ‘specificities.’ This tendency has often been satirised—the overweight caucus of the Cherokee transgender disabled lesbian faction demands a hearing on its needs—but never satirised enough. You have to have seen it really happen. From a way of being radical it very swiftly became a way of being reactionary; the Clarence Thomas hearings demonstrated this to all but the most dense and boring and selfish, but then, it was the dense and boring and selfish who had always seen identity politics as their big chance.” Letters to a Young Contrarian, Christopher Hitchens.

“Artists, of course, have always liked to think of themselves as rebels but, the truth is, as along as art remains a prestige economy of the free market – a glitzy barnacle on the side of global finance – it cannot be an effective tool for political change.” Art Will Not Save Us, Anna Khachiyan

American age laws run in an infantilizing direction. You can go to war three years before you’re allowed to drink or smoke, and seven years before you can rent a car. Our century, which just turned 25, can now do it all. It can have sex in every state, party and drive—though most Zoomers as old as the century soberly consume porn or romantasy smut at home because they can’t work a self-driving steering wheel. But at 25 American years of age, our century is also due for a quarterlife crisis. As far as this crisis concerns the ability to make good art, it’s been going on for nearly a decade, at least according to art critic Dean Kissick, who recently found himself under a fusillade of predictable outrage for gently pointing this out on the cover of Harper’s Magazine. But, in truth, haven’t all 25 years of our American century been one big identity crisis?

Consider this. At only one years old, our century was visited by an ultraviolence some post-modern dullards have called the last great work of art. Our century’s definition of art was, understandably, debauched from the cradle. In response to the trauma, the 21st Century was raised under the helicopter tutelage of the Patriot Act, the NSA and the National Security State, while also being encouraged to unleash a tyranny abroad on foreign classmates as its victimized due. At age 8 and a reformed toddler, it started to put itself together a bit, at least on the surface. It stopped roughhousing the immigrant children at recess and, like a promising young sociopath, began to diplomatically bully its classmates instead. Our century looked sharp, spoke a more articulate English, acted more deferential and diplomatic. But you never know what’s going on at home. For all the while our century was fatally increasingly its dependency on parental surveillance: that is, it began suffering from an acute addiction to the internet, a DARPA invention that enables an intimate real-time surveillance while also rewiring the surveilled’s brain to enjoy its captivity and not be able to think in long enough attention spurts to legitimately reconsider its dependency. Poor thing.

By puberty, our century began to bristle and take itself a little too seriously. It felt duty-bound to educate its doltish elders on everything it was learning at school. After learning about fascism in U.S. History, for instance, it began calling everyone a fascist. In truth, it was never the same after puberty: middle school did something strange to its ego. But as our century entered its middle-teenage years it developed a truly insufferable image of itself as possessing a superior morality and intelligence to all, and to all a goodnight: it began surveilling others. Not really so shocking when you consider that surveillance was all it knew. Besides, assuming the role of the censor and the surveiller comes with the intoxicating, flattering perk of being always correct by definition. So in its mission to rid the world of all the evil it was just learning about, our teenage century operated under Roy Cohn’s three rules for success:

1. Attack, attack, attack.

2. Never admit wrongdoing.

3. Always claim victory, even if defeated.

Defeat? Please! Our century thought it had things in the bag. Oh did it think it had things in the bag. It thought things would go on forever like this: doted upon, the celebrated apex of the social hierarchy. You know, in America anyone can become President. Oh shucks. But then, at 16, it was stood up at the prom by, get this, Roy Cohn’s own progeny. Yeah. So it lashed out. It lashed out big time. You can understand. It ousted nearly everyone from its powerful clique, from its lunch table. It got teachers fired and friends’ parents thrown in prison, while everyone looked on in terror-stricken praise and ducked for cover in nervous prostration.

Then at 20, after cannonballing recklessly through college in a steambath of self-love and self-pity, wornout by its anger and its late nights and a TON of sexual experimentation (truly, a TON), its grandfather bailed it out. The 20th Century, a corrupt old geezer made harmless seeming by distance and dementia, stepped in and put our century on a new series of pharma cocktails. Cover your mouth and draw the curtains in your room and don’t come out until I say so. You can finish college from home. What a relief.

But this sense of safety our century enjoyed did not last, could not. At 24, after putting its grandfather in an elderly home with a last vanilla ice cream cone in its hand, the house our century returns to is empty. The birthday it spends is alone. It is a night of, finally, forced reflection. Why is it that none of its relationships lately seem to last longer than four years? Why has it just gotten back together with its ex? (Yeah he’s a bruiser and a liar, but who else was there really? The woman its parents tried to arrange marriage it to?)

It’s spent the last few months alone sorting through old klediments and canvases to realize that, all this time, there has been a deferred dream under the surface. That for the last decade—and you’ve seen this coming—it’s been making bad, self-indulgent art. Lazy, unremarkable pieces of shit. A complete waste of everyone’s time. It flinches with embarrassment remembering how for years it would get very drunk at parties and force its captive audience into praise. “Ned, are you listening? This piece here forces you to interrogate various systems of power that…” It hardly needs to read Dean Kissick’s wakeup call to know what it’s buried deep down all along: The 21st Century has no talent.

But the thing is, the 21st Century might actually be mature enough, at age 25, to finally take this all in. To stop being so defensive and have a conversation about its bad art without destroying the careers and lives of the people trying to improve it. It opened itself up to this interrogation last week at the SVA Theater in New York City, in a conversation between Kissick and the hosts of the infamous Red Scare Podcast, Anna Khachiyan and Dasha Nekrasova.

Legacy media has taken several well-deserved and well-placed hits over the last several years. It’s a beatdown style first popularized by Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent and handed down to his out of wedlock heirs on the populist right, or anti-left—or, post-modern anti-woke? Regardless, this hard to define group seems to be the only ones interested in taking up Chomsky’s mantle, as most on the left have by now forfeited their legacy of being radically critical of the media, large corporations and the National Security State—a predecessor synonym for “Deep State” which is no longer believed in by the left because their political opponents believe in it now too. (For instance, Gore Vidal, the doyen of archaic progressive thought, could not go a sentence without referencing the dangers of the National Security State up until the day he died. Orwell’s law about truth in the enemy’s mouth is here on real-time display.)

But it was an outlet of legacy publishing, Harper’s Magazine, that made the conversation about bad political art possible. At dinner a few months ago, I heard someone in publishing quip, “Harper’s isn’t doin’ too well.” (No magazine is doin’ too well.) At the event at SVA Theater, a different friend in publishing whispered to me, “Harper’s is back.” If it’s back, it’s because it’s adhering to the principles of its famous Harper’s Letter, which caused as much of a row for its defense of free speech (the closest thing our civilization has to a mathematical proof of politics) as it did for the then burgeoning anti-woke Twitterati it did not ask to cosign. (I enjoyed very much watching slighted figures like Bret Weinstein try to find ways to attack a gesture he was in principle support of only because his name was not on it.)

Last month, in a sign of free speech’s recovering health, Harper’s published a cover story by art critic Dean Kissick on how contemporary politics has destroyed contemporary art. By contemporary politics, Kissick means identity politics and “wokeness.” In other words, the regnant political dogma approved by corporations (“Just do it,” swish!) and sold to faux democratic-socialist-wannabes who don’t make a move or type a Tweet without consulting consensus market trends—which, by the way, are fast changing. As applied to art, Kissick’s essay explores how this political ideology makes the specific identity of “the self more important than the expression” of the self’s art, which is of course not even an unserious definition of art, but not a definition of art at all. It is, however, a definition of institutional profiteering.

Kissick’s essay works its way methodically through the failings of the modern art world, exhibition by exhibition. The mediocrity, the pre-fabrication, the hypocrisy, and most bludgeoning of all, the lack of originality. There are summas of critique within it that make hypocrites of leftists to whom it does not give pause:

Once, we had painters of modern life; now we have painters of contemporary identities. And it is the fact of those identities—not the way they are expressed—that is understood to give value to our art.

The extent to which the art world has taken up these concerns raises another question: When the world’s most influential, best-funded exhibitions are dedicated to amplifying marginalized voices, are those voices still marginalized? They speak for the cultural mainstream, backed by institutional authority. The project of centering the previously excluded has been completed; it no longer needs to be museums’ main priority and has by now been hollowed out into a trope. These voices have lost their own unique qualities. In a world with Foreigners Everywhere, differences have flattened out and all forms of oppression have blended into one universal grief. We are bombarded with identities until they become meaningless. When everyone’s tossed together into the big salad of marginalization, otherness is made banal and abstract.

So the marginalized have become the monopoly of capital markets, the exploitative, coercive, and profiteering systems that marginalized and oppressed them in the first place, according to what is by now an archaic leftist definition of capital. In so doing, marginalized communities, which are already most vulnerable to stereotype, have become a new kind of trope: an IKEA easy assemble chair. A cheapening decoration, a canned ambience, a capitalist product. And not just capitalist, but the kind of capitalism Marxists and Libertarians revile equally: monopolistic capitalism. An economic force working against individual freedom, to say nothing of individual freedom of expression (art), something the left stopped caring about when tech monopolist surveillants started paying their bills.

In taking this much more economically than Kissick, I risk the “boring, tedious, materialist” analysis Anna warned against midway through the event. But I am holding your hand down this Marxian stroll because I don’t think leftists quite know what leftism is anymore. Not to mention it was Anna, who alongside Dasha are supposed to be unthinking MAGA shills, who already laid out this economic contradiction with unassailable logic in her essay, “Art Will Not Save Us”:

Artists, of course, have always liked to think of themselves as rebels but, the truth is, as long as art remains a prestige economy of the free market – a glitzy barnacle on the side of global finance – it cannot be an effective tool for change.

[…]

In any case, art’s cozy rapport with capital means that its potential role as a political agent was compromised long before such basic questions of transmission and circulation could even begin to be addressed. When we talk about the art world, we are always implicitly talking about the art market – or otherwise, those fringe aesthetics and grassroots communities that operate outside of its primary value index and are therefore obsolete within its organizing discursive framework. Today, the sort of dissenting viewpoints rewarded by this discourse are those that are unlikely to deviate from polite bourgeois opinion.

Besides obvious and emulatable intelligence, what is on display here is just how far right the left has shifted when it labels this kind of critique “fascist” or “racist.” If it is now right-wing and fascistic to critique capital, it is a convenient development for neo-liberalism, helping it avoid acknowledgement as equal, enthusiastic partners to the GOP in exploitation. As of late, the left’s decorative use of identity politics as brand ambassadors for voters has begun to reveal itself as a once-clever but now failing ploy to protect its flank, shield itself from its historical criticisms while pretending to address them, and continue exploiting these same groups. Consider how women, black and Latino Americans helped carry Donald Trump’s presidential victory this go-around.

Touching on a truth, Kissick touched off a controversy. I don’t mean to claim parity with Kissick, but I do mean to claim parody: if his essay went head-on at a bundle of stultifying modern hypocrisies, the controversy surrounding my Vanity Fair profile released the same week about Cormac McCarthy’s secret muse showed the constituents of this politic flail in high farce. The outrage was that I allowed a woman to refuse the dressage of an identity politic worldview that did not fit her lived experience. I rather thought my approach of recognizing a woman as the sole authority of her own private life was the feminist thing to do, but apparently it would have been much more progressive and moral if I had mansplained her life to her and conscripted her story into the very political consensus that subsequently shamed and victimized her for speaking her truth. See what I mean here by parody?

Then there was the controversy of Harper’s partnering Kissick with Anna and Dasha, hosts of the Red Scare Podcast. The podcast is infamous for, in part, supposedly switching shades of red from their early pro-Bernie “Communist” red, to the red weave of Steve Bannon’s GOP banner. They stand accused of just about everything microcelebrities in a city as charmingly, forgivably solipsistic as New York usually are. Namely opportunism, insincerity, phoniness. But in reality, they were among the first to viably break with the suffocating leftist conformity, a break that has its legitimate grievances with the corporate suppression of Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020, and the subsequent wall to wall anti-Trump melodrama of legacy media. Just for the record, in 2016 two candidates emerged with overlapping populist and anti-establishment appeal, Sanders and Trump. Only one was allowed to rise through the ranks democratically. The 2016 and 2020 primaries saw Democratic party collusion against Sanders, its most popular (but establishment-threatening) candidate, and 2024 saw the cancelling of the primary altogether under the self-satirizing slogan, “Democracy is on the line.” Only the terminally out of touch could fail to see how, in a democracy, this blatant hypocrisy and election interference would draw support away toward an opponent that was nominated twice by the unencumbered popular will of his party, running on a platform of disrupting a corrupt establishment, which the DNC just reminded everyone it was a prime exemplum of.

In truth, Red Scare operates on that exponentially growing demographic of the internet where, say, it is possible to play a game of “Who said this quote about H1B Visas, Bernie Sanders or Steve Bannon?” It is also possible to play this game between Bannon and Chomsky on the subject of imperialism. Furthermore, it is a politic where Sanders and Trump both agree on capping credit card interest rates at 10%. (This is not to draw a political or moral equivalence, but to draw attention to an interesting phenomenon which the more the left ignores, the more it utterly fails as a coalition and siphons voters.)

It’s also true that, to those who spend substantial time on Twitter, a form of mental illness I myself flirt with (some sufferers call this “brain rot”), the Red Scare podcast is algorithmically adjacent to a kind of egirl thot fascismo, or MAGA chic, that if not beginning to conclusively win the culture war, is from a phenomenological gaze winning the war on the libido. (Which amounts in part to the same thing.) This right-leaning algorithmic segment is comprised primarily of attractive young women, whether they use their real photos or not. On a medium that’s usage involves the addiction of the eye, reading attractive women talk about, among other things, fertility is a reflexively pleasing place for a mammal’s eye to scroll. The odd thing is that it is very possible to follow this scroll on Twitter from sound Ray Peat advice to blatant racism and back again.

As far as Red Scare is concerned, they seem to overlap in this territory of thirst trap nutritionists and hot, racist (semi-ironically?) Dutch nationalists by virtue of occupying a nimbus of free speech absolutism. They are allowed to say what they want, they do say what they want, and sometimes I agree with them and sometimes I do not. This seems to me a pretty healthy situation in a free society. I do not pretend to a comprehensive view of them, but I admire that the more I engage with Red Scare, the less I can define them by the old, stultifying political binaries of the past. In fact, they cannot be defined by this binary at all. I consider this a step in the right direction for human beings.

In their outrage against Harper’s, people suggested boycotting the magazine. But of course Harper’s doesn’t need the performative excisions of the left to put it under, as the whole magazine industry is getting slaughtered by the scourge of the neo-con and the neo-liberal: tech monopolism. In fact, the event began with Harper’s President and Publisher John R. MacArthur touching on the decades-long Google and Facebook ad revenue pilfering, urging attendees to subscribe to his magazine at a rate that averages out to just over a dollar a month. There was a collective grin if not eyeroll at what could be lazily called shilling if it wasn’t absolutely the unspoken and, at this stage, unknown truth. Not contemporary politics but contemporary technocrats have killed contemporary publishing.

If I did not already feel myself growing long-winded I’d say more, but let me at least say this. Google, which knows where you are right now and has access to keyword phrases in your private emails and is selling all this metadata to companies to place targeted ads at you, algorithmically funneling you into cheaper, cruder, monocultural choices and identities, is, catch your breath, also the root evil of why print journalism is in existential crisis. In one fell swoop/funding by DARPA, Google (and now Facebook) co-opted the internet ad revenue of magazines, its main profit stream, and forced the industry with subsequently winnowing budgets to gain visibility and readership not through quality but by ranking high on Google’s search result pages. Search result pages are ranked by an insidious concept called Search Engine Optimization (SEO), a set of standards and anti-writing practices that Google’s algorithms use to recognize and value “informative, authoritative” writing over human, voice-driven, stylistic writing. In such a mafioso-esque extortion of revenue, most of journalism can no longer afford to prioritize writing for an audience of humans, but instead must write for Google and its non-human, dim-witted algorithmic standards. That means no more voice or artistry, no anecdotal lead. Get to the point instantly and unambiguously because algorithms don’t do well with parsing voice or art—and now after decades huge swaths of readers don’t either. Born was the one sentence opening paragraph and the kneejerk hot-take. The only reason why generative AI technologies like ChatGPT have a chance of replacing certain types of writing is because writing has been devolving toward AI’s bland, algorithmic, encyclopedial style for decades. Should publishing perish, Google AI and Grok will merely produce content by aggregating and plagiarizing what’s already been written, and what’s being posted on social media by anonymous strangers, and we will enter the final stagnation of culture and our ultimate death rattle. So unroll your eyes, fight “brain rot,” and do subscribe to print, for the love of God. (This message was not paid for by Harper’s.)

Now, the fact that the conversation didn’t live up to the predictable controversy of both the article and the partnering with Red Scare was not a flaw. It felt culturally healthy that a legacy mag and a non-legacy podcast had a sold-out, mild-mannered discussion about a subject they’re in good-faith consensus on. Shocking art critics by not being shocking – isn’t that just the Red Scare ladies keeping everyone on their toes? Not to mention that just as the discussion got into its best collective flow, the organizers to whom I bore Google-related sympathies brutishly wrapped things up against the panelists’ will, because they had a dinner they needed to go to. (If anything, I think this was the most controversial moment of the night.)

But if reviewers are let down because they didn’t come away from a Red Scare event with their dreamed-of “callous pull-quotes, cavalier defenses of cancelled artists and caustic hot takes about why art can’t change the world,” then perhaps they should reconsider their dreams, to say nothing of their preconceived notions about the podcast. This style of criticism is unserious and sets up a bad faith, lose-lose scenario: when you say something I think is fascist, you’re wrong and I’ll slam you. When you do the opposite, when you don’t say something I consider fascist and fail to titillate my prejudices against you, you’re also wrong and boring.

First impressions, too, are often wrong and boring. What I initially thought was a good but slow burn of a conversation was, as I relistened to my recording, nuanced and cerebral from the jump. Much more nuanced and, in fact, charitable to identitarian art than I’ve been thus far in this essay.

The discussion began with Anna pressing Kissick on the moral fatigue of the present state of political art. As Kissick explained, it’s not that identity politics is by definition incapable of making art (though admittedly it is not the most interesting to him), but that after nearly a decade in which it has been the outright dominant form, its framing as “urgent” and “radical” has become exhausted and tropish, and the works derivative and ponderous. He pointed out that this is merely the lifespan of any movement that pretends to urgency and is then promptly, endlessly dominant and unchallenged. In exhausting its once legitimate pretenses, political art has fallen inevitably into the self-interested, stultifying talents of capitalist careerists and money launderers whose job it is to drive profit and protect their salaries in the art world.

Anna, supposedly a right-wing Nazi “edgelord,” then responded by outright dismissing the lazy rightist critique that art’s crisis has been the result of wokeness and the culture war. Rather than being an ideological problem, she sees it as historical and technological, with the post-internet movement that preceded woke art forcing artists to compete online and on social media. If I may sum up several points here, in which Dasha was, contrary to some criticism, not mostly quiet, the effects of this switch to the internet have been the following: Gallery art was forced to look as good on the internet as it did in person, which besides being an arbitrary hindrance was the main criticism of post-internet art in the first place: that in prioritizing an internet aesthetic it looked “like shit” in real life; shifting the locus of art to the internet, an institution-undermining medium, encouraged an increasing loss of faith in the institutional structure of the art world and galleries; where once the art world was upstream of “discourse” (an utterly useless word in my opinion) and set “trends” (another), it is now downstream of a (schizophrenic—my take) online discourse and series of narratives where, as Dasha pointed out, social justice warrior narratives have been the dominant algorithmic trend. This has left the art world beholden to the internet trends that tech oligarchs prioritize which, to quote myself, is obviously an irresponsible way to value anything, especially art. In doing this, I might add, curators’ fingers are not on the pulse of organic art trends, but rather on the cold, 0 BPM wrist of Mark Zuckerberg.

To this point on being beholden, Kissick agreed and recalled one of the most intriguing observations of his essay. “I think they’re [art galleries] following narratives that are perpetuated online. The kind of art that is a big part of what I’m writing about – it’s not just the idea that art should adhere to certain ideas of social justice, but the forms of art that are chosen to do that are very conservative. Not politically conservative, but aesthetically, formally conservative. That’s a strange decision.” He refers here to the recycled use by contemporary artists of old forms and styles of art, infused with internet-age political leftism and political identities. Art that purports to be progressive is formally regressive. Which draws an odd contrast to the current crisis in contemporary literature, which stems in part from the annihilation, disregard and ignorance of the canon and its old forms and styles. Would we were so lucky that mainstream novelists were rehashing stream of consciousness or surrealism or existentialism! Instead we suffer under a very uniform, bland social realism interlarded with internet age morality discourse (a shudder).

This dichotomy may point to the fact that literature—or literary fiction as it’s called because it no longer has pretense to being on par with its predecessor: literature—has exited its post-modern recycling period. The art world, in contrast, still seems post-modern in its tendencies (which Kissick later educated me on in the conversation below). And a post-modern territory is exactly where the conversation resituated.

Again, being far more generous than his critics would have it, Kissick argued that even when modern political art is good, its top-down institutional framing is one that focuses on identity first, something that patronizes the artist. What precedes the piece, or what the viewer is explicitly encouraged to value about the work, is that the artist is, say, indigenous or queer or both. As Dasha pointed out, this incessant framing rids the artist of enigma and mystique, which is of course the impetus behind biography and at least half the general or obsessive interest in any artist, for better or worse. (Mostly worse.) Instead of the art, the identities of the artists comprise the press releases and wall texts of the installations, which, by the way, are the only things that make the art comprehensible.

I’ll let Kissick give an example of this. He describes many in his essay, concluding with my favorite at the Whitney Biennial:

Elsewhere were Karyn Olivier’s assemblage of found lobster traps from Maine, pot warp, and buoys hanging from a rope made of salt, which “invokes a memory of the work’s oceanic origin but also of the practice of trading salt for enslaved people in Ancient Greece.”

Needless to say, it was hard to glean any of these alleged meanings from the works themselves. Rather, they could be discovered only from the descriptions on the wall, which read like the everything-is-connected code-breaking ravings of an overeducated cabal convinced that a hidden semiotic language of resistance lies below everyday objects, camera angles, orientations, and gestures made so very many times before.

Or in Dasha’s words, “this work forces the viewer to interrogate several power dynamics” but in reality “is the worst thing you’ve ever seen in your fucking life.” This mode of having to explain and tell the viewer explicitly what it is they’re looking at is not just anti-artistic or patronizing to both artist and viewer, they agreed, but also merely propagates the top-down institutional control of the art world as an institution. It is not radical and it does nothing to change the status-quo. Stop me when I get to fascism. How is this not a leftist critique?

But the supremacy of wall text qua childishly-explicit-theoretical-underpinnings over the art itself is not the invention of, say, incomprehensible woke sculpture. It is the invention of post-modern art, conceptual and abstract. Now, there is good kind of abstract and conceptual art, and then there are yellow triangles painted against an ungessoed canvas that express the post-impressionist breakdown of shape and proportionality into their Euclidean roots of… sorry, I’ve grown bored. Identity politics, as heir to the bad French translations of pretentious post-modern “theorists,” naturally inherited post-modernism’s syntax and framing structures. Dasha’s quip, “this work forces the viewer to interrogate several power dynamics,” can just as well serve as the dispiriting explanation to a bad piece of non-political, late 20th Century pottery as it can to a piece of modern political art.

The only critique I can quite muster for the talk is that post-modernism itself was missing from its crosshairs. But this is unfair of me, as post-modernism itself was beyond the mandate of the panel and merely my own personal scapegoat for all the world’s ills. But I think there is sapience and, dare I say it, “urgency” behind my bias against post-modernism as a movement. For it is the exhaustion of post-modernism, the banal and facile refutation of all truths and dogmas, that has given birth to the new censuring orthodoxy: wokeness. It is spurious whatever form this orthodoxy was to take, for an orthodoxy of any kind was going to take after the sophistry of post-modernism exhausted itself. It is a natural law of imperial civilizations that when establishments, traditions and old long-reigning orthodoxies are razed to the ground from within, it will inevitably give birth to a fervorous new orthodoxy. It was this way before in ancient Greece and Rome.

There’s a certain kind of person who relates everything to Ancient Rome, and I’m not just thinking of a candid Richard Nixon. This type of Dick is only annoying when they’re wrong, so you’ll excuse me in the attempt at summarizing several hundred of pages of The History of Western Philosophy by Sir Bertrand Russell, who was only ever right. The enlightened age of Greek philosophy can be defined as an age of philosophers who were also statesmen with the power to write laws and effect governance of their city states. In this age, philosophy had direct bearing on governance. (The only time the world would see this dynamic again was during the American Revolution and the earliest days of American polity.) This optimistic age broke down in unison with the subsuming of the city state into the larger Hellenistic Greek empire, and the loss of individual and state efficacy. As philosophers could no longer affect political change or power, they began to look solipsistically within. (“I can’t change the world, but I can change the world in me,” to quote Bono.) They became, in a world which they could not control, very cynical. Thus arose, no surprise here, the Sceptics and Cynics, the ancient world’s post-modernists who argued against the possibilities of truth and all received tradition. It was hard not to be skeptical and cynical of philosophy and civilization when it had become efficaciously meaningless, purely solipsistic, and all received tradition null. This confluence of solipsism and cynicism, perfected during the deflowering of Rome’s republic into dictatorial empire, left ancient institutions defenseless against the invasion of the equally solipsistic orthodoxy of Christianity. (Again, “I can’t change the world, but I can change the world in me” as the refrain of individual salvation.) As Rome’s empire crumbled under several large systemic crises, statesmen prioritized arguments on points of arbitrary Christian doctrine, such as what kind of female dress was allowed in public.

Does this not ring any American bells, in our post-republic, post-modern era of elected, rotating emperors?

As far as America’s decline mirrors ancient democracies’, we have moved through these philosophical cycles at an accelerated pace. (It would of course be boring and give far too much credence to banal simulation theorists if we matched up identically with the patterns of the past.) What we stare down now is collapse. But in a globally interconnected world, singular collapse is not quite probable. Thus, I find it entirely possible that we may be able to wrap up our decade of new orthodoxy and move beyond it, while retaining its benefits (such as empathy and an eye for inequity, which wokeness failed by being totalitarian and doctrinaire in its modes, and naïve in its solutions: abolishing all prisons is not a serious or realistic way to reform a system of racist incarceration).

We must fall back on first principles. Individual genius is the prime mover of all the arts, and “schools” and “movements” often grow up around groups of contemporary individuals in the non-artists’ attempt to define and assimilate what moves them about their work. Audiences will always try to find ways to project contemporary politics and trends onto art, which the artist must resist being captured and influenced by. We can get back there. But to do this we will need to follow Kissick and Red Scare’s advice in prioritizing art over artist. For political art makes itself hostage to political fortunes, which come and go—definitively they go and are unremembered. Therefore, it must have only a secondary or, to be still more safe, tertiary involvement in creation. We will need to stop calling things “theories” which are scientifically unprovable sociological speculations briefly in fashion and doomed like all political trends to the dustbin. We will need more discussions like this one between legacy and non-legacy outlets, which show a conversation across platforms and political beliefs is still possible and necessary. This dialectic is our pulsebeat as a free, healthy society.

But we will also need to move beyond post-modernism, including Dasha’s affectionate dressing of Trump as a Warholian pop-art figure, and Anna’s tweet, quoted by Kissick at the event, “Very few things made today will have cultural significance, because we’re past the era of cultural significance.” These are not false statements: they are realist statements in cynical times, post-modern truths in an anti-truth environment. But taking Warhol too seriously is a form of defeatism. The first question from the audience after the talk about whether a social media sex-worker’s recent “feat” of sleeping with 100 men in one day was a work of performance art, shows better than anything how post-modernism will invariably bring a civilization’s art from Dada to nada. As an ethos, as questions, they are not optimistic enough. And there is a lot to be optimistic about.

Namely, that for such a supposedly controversial take on contemporary art, I do not personally know anyone who doesn’t agree with all three of the panelists, whether they are fans of Red Scare or not. (For lack of a better political spectrum, the many people I’ve spoken to are on the left—after all, they read Harper’s.) We are at a point in contemporary culture where we can rightly say that the silent majority has moved on from identity-first art, and is in fact less and less silent about it. Red Scare is owed a lot of credit for this: not just in breaking through censorship but encouraging the refutation of self-censorship amongst a young audience impressionable to surveillance and sociologies of suppression. Harper’s is moving in the right direction by recognizing this and giving a voice to critics like Kissick.

I belong personally to a barely vocal minority that believes that politics of any persuasion have no place in art at all. I am, like Nabokov (if I may try to appear kindred for just a moment), only interested in individual genius. And I am prepared to argue that unseduceable posterity takes the same enlightened prejudice. And that individuals of various identities, ethnicities, genders, sexualities, have all produced works of non-identity-politic genius and will continue to. But political art is for major satirists and minor artists. As a sole and primary impetus it is for hacks and dies from memory unlamented. The American dustbin is full of once oppressively lauded novels and plays and poems of supposed socio-political import that did nothing but prove the credulity and bad taste of America’s endless cycles of Puritan publics. (For the record, these works to which I refer span the gamut of our inadequate political spectrum.)

This is admittedly an extreme view, or minority view, one which I find no alternative to by the end of Anna’s “Art Won’t Save Us,” and one which Dean Kissick is much more charitable about. I understood charity to be in his nature as he fended off five or six handlers trying to usher him off to a much deserved celebratory dinner at the Chelsea Hotel, while I put these and other considerations to him.

Thank you, Dean.

INTERVIEW WITH DEAN KISSICK 1/9/25, New York City.

VINCENZO BARNEY: The other half of really terrible art out there, besides what you cover in your piece, seems to me bad, bullshit post-modern art. And I feel like across the arts post-modernism as a movement, whether it was a legitimate one or not, has sort of exhausted itself. I’m curious whether you agree with that. What era are we in? Are we still in a post-modern era?

DEAN KISSICK: That’s a hard question. But maybe I can skirt the question of post-modernism a bit. Post-modernism is complicated and hard to define. Even to talk to about a post-modern period is hazy. But my piece talks a lot about pastiche. I think it’s a bad thing. There’s a lot of art and culture that is very backwards-looking, remaking the past, remaking new culture out of old culture. I think that’s bad for culture. And that is very post-modern. If you look at Frederic Jameson’s famous quotes about post-modernism, they apply perfectly. He talks about a culture that is just pastiche. He talks about an art of combinations. He says that there are no new styles, all people do is endlessly recombine styles of the past. That’s definitely happening in the exhibitions I’m critiquing, the Venice Biennale for instance. So I think we are in a post-modern moment in that sense.

But you said in your question, “What moment are we in now?” I trace in this essay the modern art moment. And it’s a succession of different movements, each succeeding from the last, looking towards the future, and at some point that turns into contemporary art, which is supposed to be the end of art. Danto says that’s the end of art. And it’s this endless consumption of the present, taking everything in the present and making everything into art. And I do think we seem to have moved into a different moment past that that is so backwards-looking. Modern art looking to the future. Contemporary art looking to the present, and it seems that at some point things have gotten very backwards-looking which is very post-modern.

I don’t know if it deserves a new term like “post-contemporary art” but I do think that we should acknowledge that what we used to call contemporary art and what we call contemporary art now are different things. And maybe they relate to this sense of time being completely scrambled which is very online and social-media based and post-modern.

BARNEY: You mentioned in the talk a friend of yours asking, “What’s going to come next when this trend is over?” Do you think we have a trend-anxiety? Are we too anxious for trends, for categories and movements?

KISSICK: I mean there hasn’t been a real movement in a long time. Then again you could say that this identity-based art is a movement, an important new movement. A new way of thinking about looking at art. But art’s not just about trends, in this moment past movements. And I get criticized about this all the time, like I’m some desperate trend hunter, always looking for a new thing, incredibly superficial. Some people say it’s a fascistic way, post-Adorno, of looking at culture. But it’s not that way. There should be something new. Not even just new, but something should explore the present. I think we’re past the trend moment and it’s restrictive to focus on “What’s new?” “What’s the trend?” But we’re in this moment where everyone is nostalgic, everyone is looking back. I’m not asking for a modernist creation of the future, but let’s at least talk and think more about the conditions of the present. Let’s just explore because this is a crazy time to be alive. You know it, you’ve experienced it. That’s not an experience you could’ve had ten years ago, right?

BARNEY: Totally. The internet’s opened up access to a discourse that maybe we shouldn’t even necessarily be aware of. Like when the piece came out, it’s like, why do we care about what Joe Shmo, some random guy somewhere in the country says about this? In the era of great art, great literature, great magazine writing you wouldn’t know necessarily about every single little comment made about you. There wouldn’t be a virality attached to every little comment the way there is now. Is that holding back art? Is this holding back the gate keepers and decision makers, the awareness of what might be said by someone whose completely anonymous?

KISSICK: Yes, I think so, but it’s completely in your own head. I was talking about the demon in my head to do with cancel culture. But it’s completely in your head. This is the curse of the millennial, to think and worry about what other people think.

BARNEY: You wanna smoke?

KISSICK: Maybe a cigarette would be good after that. (Pause for inhale.) I do think that it’s a big problem with millennials in particular to care way too much about what other people think, and most of the caring is completely imaginary. Because most people art not critiquing your work, cancelling you, paying attention to you, at all. Maybe they were with you for a week, but you seem fine. But that can kind of turn into second-guessing yourself. Instead of just thinking “What do I think?” you’re thinking “How will this be perceived?” And that’s anathema to trying to thinking freely and creatively. Trying to write honestly.

BARNEY: I guess that gets back to a central question in art of how much should you even be concerned about an audience? Like Cormac McCarthy who I wrote about was writing in total obscurity, he was destitute, and he wrote some of the greatest works in American literature in that state of having practically zero audience. He was unaware of what his readers thought of him, in fact his readership was very low and he was out of print at that time. So how much should an artist be concerned about an audience?

KISSICK: I don’t think they should be that concerned. That’s not saying you can’t be, but I don’t think they should be. I like this idea that you’re making work only for yourself. In practice you’re probably making work for three or four other people, if that. A couple people you are connected to, talking to.

BARNEY: Who is really at fault for where we’re at right now?

KISSICK: Of course not everyone is. But many people are. Artists and non-artists. That’s a consequence of the network society. You’re thinking in this kind of collective way. You’re being influenced. It didn’t used to be like that. You have this constant flow of algorithmically created consensus fed to you every day. For awhile, but maybe not anymore, you had a paranoia about it.

BARNEY: Is it possible to break free of those constraints without breaking free of that entire environment?

KISSICK: Of course, because it’s in people’s heads. You wrote something that annoyed all these people, or some people, and that’s gonna create your career. It has the opposite effect. I read the responses but I don’t know, maybe it’s a good thing that in I couldn’t name a criticism of my piece that really stuck. [IN REFERENCE TO AN AUDIENCE QUESTION ABOUT WHAT CRITICISM OF HIS PIECE STUCK.]

BARNEY: I agree. I’ll ask you one more question. Is it possible to make great political art? Is political art ever as great and timeless as the best non-political art?

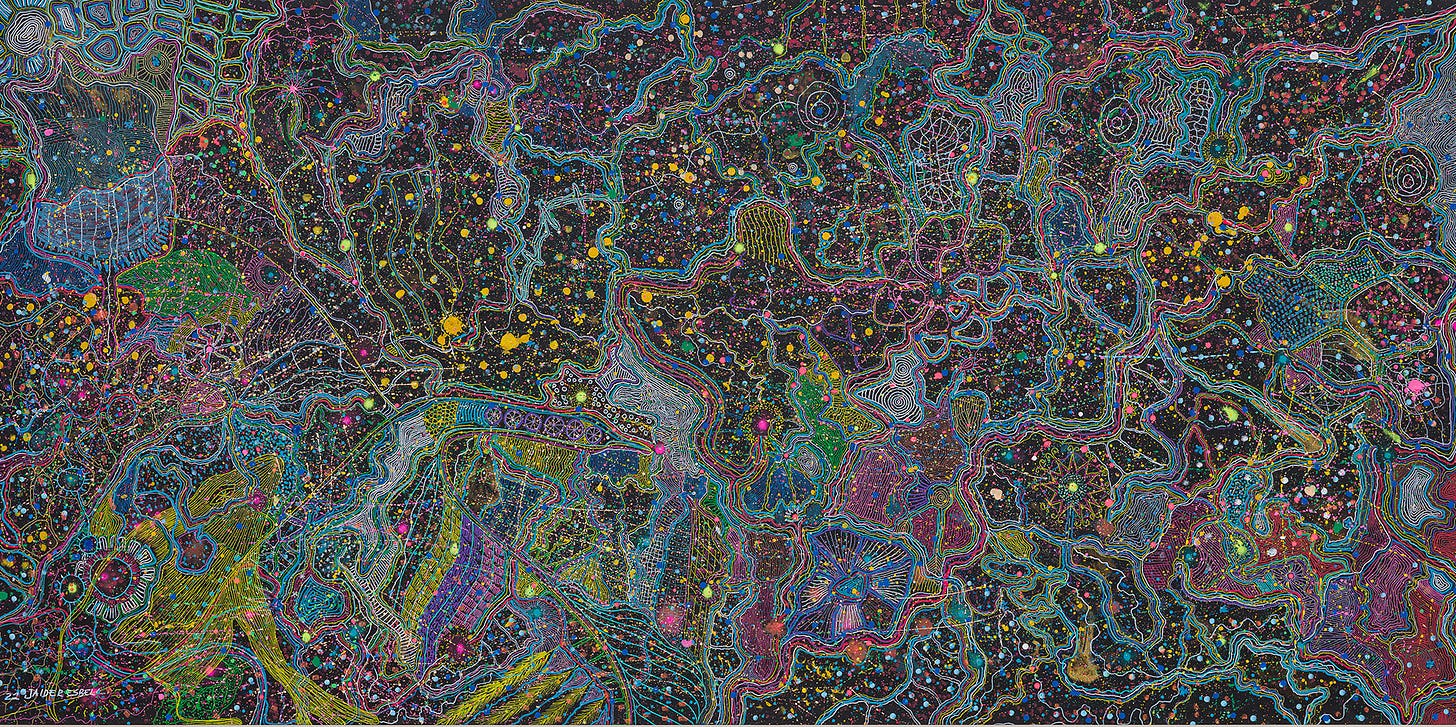

KISSICK: Yes, there is great political art! And sure, it’s greatness can last. First example that comes to mind here is Picasso’s Guernica. Goya’s Disasters of War, too. For indigenous contemporary art, Jaider Esbell’s paintings are excellent. One could argue that his paintings are not exactly political, but he was a very politically motivated figure.

great post barney love it, keep going let me know if you want to do an event like this yourself sometime downtown

“political art is for major satirists and minor artists. As a sole and primary impetus it is for hacks and dies from memory unlamented.”

Yes, this is usually true.

And you’re also right that the judgment of history has consistently concurred.

Lots to think about in this essay and the larger issues raised.

The point in the final transcribed interview about Cormac McCarthy, working in isolation and simply bashing away at his novels without regard to the fact that no one was reading them, yet anyway, is inspiring, and people who really want to make art, or write, should keep it in mind as a role model. It’s a hard life with no guarantees. And you may starve to death. But if it’s what you put on this earth to do, you should do it anyway.